Overview

The other day, I had an animated conversation with a friend about how “Christopher Nolan’s films are difficult, but fascinating”. We ended up rewatching Interstellar, and this is the continuation of that.

August always reminds me of the atomic bombings of 1945. I thought it was a fitting occasion, so I watched the movie about the “Father of the Atomic Bomb.”

Summary

- [Brilliant Student Years] Robert Oppenheimer (born 1904) graduated top of his class from Harvard University, then went on to study at the University of Cambridge.

- [Finding His Calling in Theoretical Physics] For some reason, Oppenheimer was terrible at experiments and was constantly ridiculed, which frustrated him. Niels Bohr (born 1885) advised him to pursue theoretical physics instead, and there he truly shone. The film doesn’t mention it, but around this time he published the famous Born–Oppenheimer approximation.

- [A Popular Physics Professor in His Homeland] Although physics at the time was centered in Europe and he was encouraged to work there, Oppenheimer became a professor at the University of California, Berkeley. There, he became extremely popular. This was the 1930s. Germany announced the discovery of nuclear fission, and Hitler invaded Poland, which increased Oppenheimer’s interest in the war as a Jewish scientist.

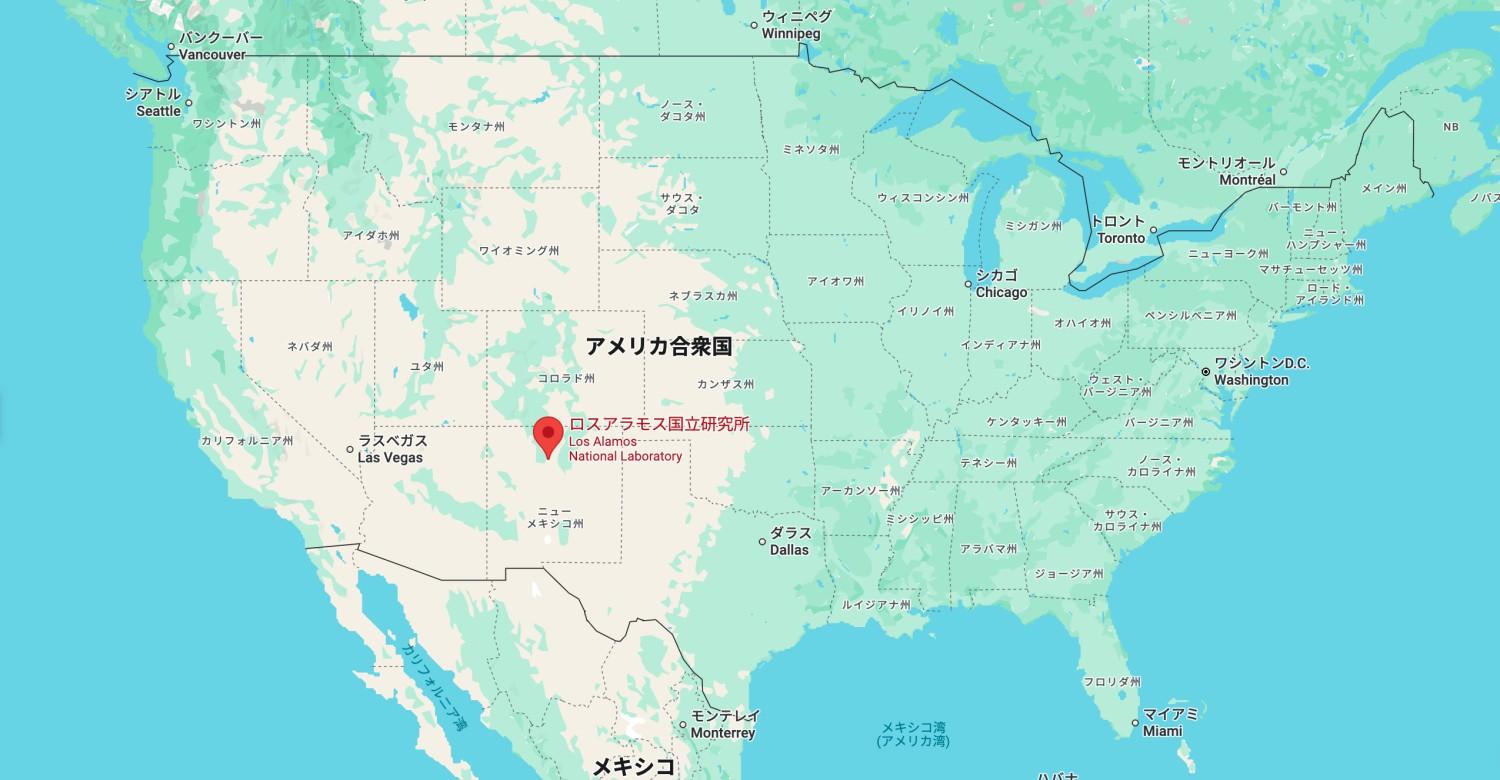

- [The Manhattan Project and the Founding of Los Alamos] Colonel Leslie Groves, leader of the “Manhattan Project,” appointed Oppenheimer as head of the scientific division. Oppenheimer was told to “build a town” for the project. He gathered members and built the town of Los Alamos in New Mexico, where the atomic bomb would be developed—and where dissent was silenced.

- [Moral Concerns Brushed Aside with ‘Better Than the Nazis’] Many scientists, including his former mentor Bohr, questioned the development of the bomb. But most doubts were resolved with the idea that “it must not be the Nazis.”

- “Is the culmination of 300 years of physics just a weapon of mass destruction?”

- “You are America’s Prometheus.”

- “Humanity is not ready to possess nuclear weapons.”

- [Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki] World War II ended with Japan’s unconditional surrender, and Oppenheimer became a war hero. Some scientists celebrated, while others were devastated that their creation had killed so many civilians. Oppenheimer began to have visions of people burning to death from the bomb.

- [President Truman’s Outrage] Oppenheimer spoke of returning Los Alamos land to its original Native inhabitants and told the president, “I feel my hands are bloodstained.” Truman exploded in anger, saying, “Don’t ever let that crybaby in here again.” At Los Alamos’s farewell ceremony, Oppenheimer gave a speech saying, “Los Alamos will be cursed.”

- [Continued Support for International Control of the Bomb] Oppenheimer consistently worried that competition between nations would drive endless nuclear weapons development, and he supported worldwide control.

- [Clash with Lewis Strauss] In 1949, during congressional hearings, Oppenheimer ridiculed politician Lewis Strauss, who would hold a grudge against him ever after.

- [The Oppenheimer Hearing and Removal from Public Office] In 1954, Strauss orchestrated a hearing out of revenge. Oppenheimer could not clear himself of suspicion of ties to the Communist Party (which at the time meant being seen as a Soviet spy), and he was removed from his official positions.

- In 1959, Strauss sought a promotion but was exposed as the man behind the Oppenheimer affair, ending his career ambitions.

- [Awarded the Enrico Fermi Award] Not mentioned in the film, but in 1963 the government acknowledged its wrongdoing in the Oppenheimer affair and sought to restore his honor.

Impressions

-

I realized Oppenheimer lived in the same era as Albert Einstein and Hideki Yukawa! In one scene, Oppenheimer says, “I’m going to talk to Einstein”—and I was thrilled.

-

Albert Einstein (born 1879)

- Robert Oppenheimer (born 1904)

- Hideki Yukawa (born 1907)

- Yukawa doesn’t appear in the film, but reading Wikipedia, I learned they had interactions, which moved me.

- Throughout the film, the themes of “better than letting the Nazis develop the bomb first” and “the reluctance to be involved in creating a weapon of mass destruction” were powerfully present. It was a painful three hours. Oppenheimer outwardly inspired scientists so well that he was called “the salesman of science” and even “a politician who abandoned physics long ago.” But the film showed that he was always in conflict internally.

- What made Oppenheimer the “father of the atomic bomb” wasn’t just genius, but being a genius willing to make the decision to build mass destruction. Of all geniuses, those whose decisions change the world make history.

- Up to a point, I had the same excitement I felt watching The Imitation Game, following the life of a genius scientist.

- (2019-08-19) Movie "The Imitation Game"

- But when Japan’s name began appearing in the film, I naturally started feeling heavier. Among all my experiences watching “based on a true story” films, this may have been the first time I felt that way. An intense experience.

- President Truman is considered “the president who ended the war early and saved American soldiers’ lives.” I thought, “What the heck? Outrageous!” But reading articles online, I found claims like “Truman never intended to drop it on a city full of civilians” and “he couldn’t publicly reverse the decision, so he had to carry it for life”, or that his anger toward Oppenheimer came from “my hands are far more bloodstained than yours.” That’s when I stopped researching further.

- I think that feeling indignation and helplessness from one’s own investigation, recognizing that the full truth may never be known, and carrying that uncertainty—this is what it means to study history.

- From a filmmaking perspective, the depiction of the first nuclear test, the “Trinity Test,” was incredible. There was the political tension—failure would mean total disgrace—and also Edward Teller’s proposed “thermonuclear runaway,” the possibility that igniting the atmosphere could destroy the entire Earth. In fiction, there’s the sekai-kei genre, where the fate of the world hinges on the relationship between just a few ordinary kids. But in that scene, the fate of the entire world truly rested on one small red button. The real sekai-kei, and absolutely terrifying.

Leaving the heavy thoughts aside, here are some great dramatic moments:

“Why cling to one doctrine? I want to sway.” “I want to sway too.”

Intellectually romantic.

“You’re not complicated. You’re just not getting enough sex.”

Love it when female characters drop lines like this.

“Don’t push away the only person who understands you. You’ll need them someday.”

Said to the charging-ahead Oppenheimer by a friend. Just plain good.

“Is the culmination of physics just a weapon of mass destruction?” “But it must not be the Nazis.”

Heavy, but cool. I think Oppenheimer’s greatness was in not stopping at “I don’t know,” but finding an answer and moving forward. In politics, you need to decide and act. Oppenheimer could do that. That’s why he became Los Alamos’s leader—and the “Father of the Atomic Bomb.”

“You commit a sin and then want sympathy for the result? Get a grip.”

Powerful. A line from Oppenheimer’s wife, Katherine Harrison (nickname Kitty). It’s an incredible encouragement: I won’t share your pain; you face it, confront it, and overcome it yourself. From the context, you might think it’s about the bomb, but it’s actually about Oppenheimer’s earlier involvement with a woman who died.

So, I wrote the above summary while reading Wikipedia, but wow—Nolan’s films are tough! Every time the visuals turned black-and-white, I panicked: “Ahhh, stop shuffling the timeline!”