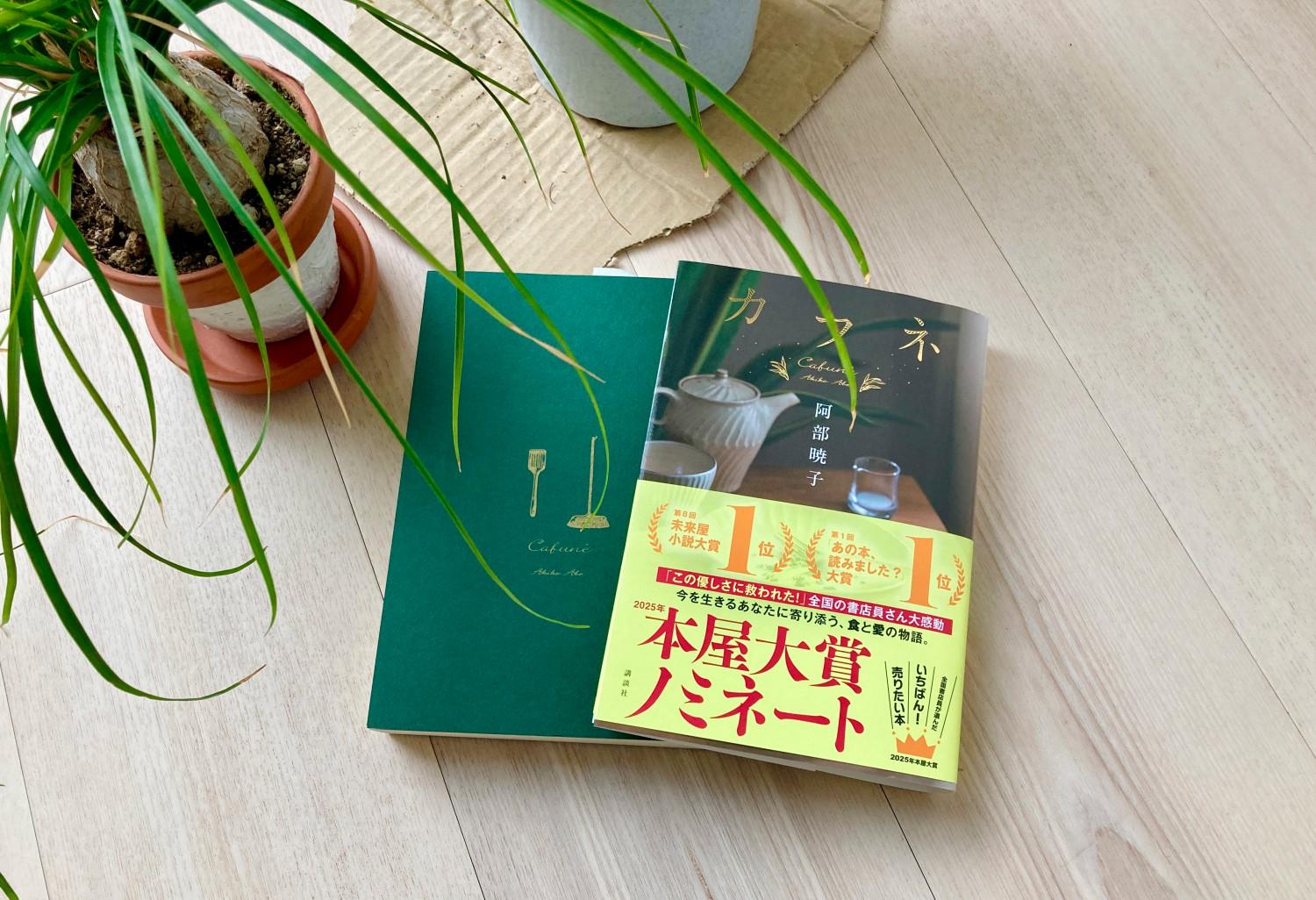

Overview

A friend recommended it, so I read this. I’ll write the summary and my impressions.

Summary

- Nomiya Haruhiko-kun:

- In his twenties, he dies of natural causes at home.

- He lived so much to accommodate others that he lost sight of what he himself wanted. As a result, he was loved by everyone and healed countless people.

- To reassure his parents, he introduced his friend Onodera Setsuna-san as his girlfriend to the family.

- Nomiya Kōko-san:

- A forty-year-old who isn’t particularly beautiful or especially beloved, but has carved her path in life through indomitable will and effort. She works as a deposit officer at the Hachioji branch of the Tokyo Legal Affairs Bureau.

- Emotionally shattered by her beloved brother’s death, devastated further by divorce from her loving husband, with worthless parents, she falls into alcohol dependency.

- When she’s at her lowest, Onodera Setsuna-san saves her, and Kōko, in turn, wants to help Setsuna.

- Takita Kimitaka-kun:

- A child-loving, earnest man working for children’s rights.

- He wanted to make Kōko happy, but their marriage became difficult because Kōko wanted children, so they divorced. Being sincere, he even gave her an apartment as an apology.

- Onodera Setsuna-san:

- Tall, with sharp eyes, insanely skilled at cooking, a child of a parent’s suicide, and embodying a “what’s the point—everything ends if you die” mindset in her twenties.

- She suffers from chronic myelogenous leukemia and often feels unwell.

- Though she’s the type to avoid relationships, she can’t leave Kōko when she’s so broken. She cooks incredibly delicious meals for her, throws away all her long cans of alcohol, invites her to volunteer with a housekeeping service, and helps her get back on her feet.

- Nomiya Sakurako-san and her husband:

- Parents of Kōko and Haruhiko. Terrible people. They sigh at Kōko when she’s broken, and after Haruhiko’s death, treat Kōko like a convenient substitute to offload tasks onto—driving her crazy.

Impressions

The comedic and fun dynamic between Kōko-san and Setsuna-san

- It’s hilarious that Kōko-san, more than ten years older, has her long can of alcohol thrown away by a younger woman.

- Even funnier that it becomes a running joke between them: “Is there a person who does something like that?” “If you’d like, shall we go to the washroom? We can meet right away.”

- Their agreement about calorie-exploding devilish food: “To live, you sometimes have to sell your soul to the devil.”

- And Setsuna-san’s jab: “You are a national public servant, after all. Don’t forget who you really are.”

About “Enough already”

- When talking about her estranged parents and memories of her beloved brother, Kōko-san felt this phrase.

- I found the sentiment of “enough already” toward youthful anger and dissatisfaction quite appealing. It reminded me of what I felt reading “Risuka 4.” Maybe I’m at an age where that sort of thing resonates more.

- But “Cafune” doesn’t end there. These parents were truly unpleasant.

Huh? Seriously? Is antinatalism gaining mainstream acceptance?

- Setsuna-san: “I don’t know if being born is a good thing. You can’t let a child choose their environment, yet you force them to live decades in this world that’s falling apart. I think that’s extremely unfair.”

- Kimitaka-kun: “I think being born and being alive is suffering. All children are born from their parents’ desires, and many are mistreated after birth. To me, having a child means creating another person who will suffer misfortune in this world.”

The fact that this book is popular must mean that, to some extent, this idea is accepted among the current generation, right? I was surprised. I totally agree! Everyone! I mean, that drawing below expresses this idea too!

In my experience, this way of thinking is often rejected. And the grounds for that rejection are usually something like “Well, I’m not unhappy,” which is just based on personal experience. But this whole argument assumes “we don’t know how the person being born will feel,” so using personal experience as the basis is just foolish. Eventually, I stopped bringing this topic up in conversation.

Seeing this topic addressed in “Cafune,” I wondered if maybe I’ve been too cautious about it.

That said, there was one thing that caught my attention in “Cafune.” The two characters who hold this view either have illnesses or have suffered painful pasts. Of course, giving characters a background is natural in fiction, but it could give the false impression that this worldview only comes from trauma. In reality, it’s a logical perspective, but it’s sometimes portrayed as if it’s built purely on emotion. I think it's best to avoid structures that could cause such misunderstandings.

Also, this way of thinking might lead to resentment toward one’s own parents, but “Cafune” doesn’t go that far. Maybe that’s where it strikes a balance.